Fat in the food we eat, whether from vegetable foods or from animal origin, comes in three main categories: saturated, monounsaturated, or polyunsaturated.

In order to make the best choices we need to know a little about the differences between fats, and the different effects they have on us after we’ve swallowed them.

This is a simplified overview of the fats we get in our meals, and I’ll keep it brief.

Basics

Each type of fat is composed of building blocks called fatty acids. The fatty acids are chains of carbon atoms linked together, and the chains themselves can be of varying lengths.

The links holding the carbon atoms together are called bonds, and bonds can be single or double.

The number of carbon atoms, and the number and type of bonds a fatty acid has, determine what sort of fat it is, what it looks like, and how it’s used in the body’s systems.

Saturated fat

A saturated fat has its carbon atoms joined by single bonds, with hydrogen atoms attached to all the carbon atoms. There is no place to attach any more hydrogen, so the fat is said to be completely saturated (with hydrogen).

It looks a bit like this, where C is carbon, H is hydrogen, and the lines are the single bonds:

H H H H H H H H H H H H

| | | | | | | | | | | |

-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-

| | | | | | | | | | | |

H H H H H H H H H H H H

Examples of fats in which saturated fat dominates are lard, tallow, butter, coconut oil, and palm kernel oil. They are very stable, and have a long shelf life.

They’re also best for frying, because the carbon atoms are already occupied (by hydrogen atoms) and there’s no unoccupied carbon atom where free radicals could attach themselves.

Unsaturated fat

At the other end of the spectrum, a completely unsaturated fat is made of carbon atoms joined by double bonds, leaving no place for hydrogen to attach.

It’s not saturated with hydrogen and is therefore said to be unsaturated. Would look a bit like this:

C=C=C=C=C=C=C=C=C=C=C=C

Monounsaturated fat

In a monounsaturated fat, the carbon atoms are joined together by single bonds, except for one pair, which are joined by a double bond.

Hydrogen atoms are attached everywhere, except at that one double bond.

That one double bond is unsaturated (no hydrogen attached) so it’s said to be a monounsaturated fat (mono meaning one). Looks a bit like this:

H H H H H H H H H H

| | | | | | | | | |

-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C=C

| | | | | | | | | |

H H H H H H H H H H

Olive oil is an example of an oil that contains predominantly monounsaturated fat. It’s liquid at room temperature and may go a bit cloudy in the fridge.

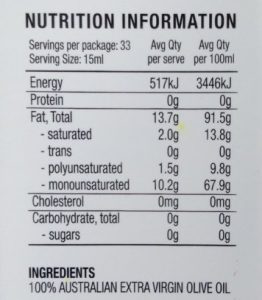

I used the word ‘predominantly’ because all food oils are composed of varying amounts of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Here’s the label from our olive oil:

As you can see, this olive oil is 67.9% monounsaturated, 13.8% saturated, and 9.8% polyunsaturated. There are no trans fats.

The largest group is monounsaturated, so olive oil is normally referred to as a monounsaturated oil.

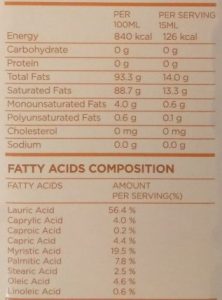

For comparison, here’s the label from our coconut oil:

This coconut oil contains 4.0% monounsaturated, 88.7% saturated, and 0.6% polyunsaturated fatty acids. The predominant group is saturated, so coconut oil is usually known as a saturated oil.

Frying with olive oil

Because the double bonds in the monounsaturated and polyunsaturated portions of olive oil can be opened by the energy from the heat of frying, free radicals have a chance to latch on. For this reason, olive oil is not suitable in the frying pan.

Best enjoy it cold, drizzled over salads and vegetables.

Polyunsaturated fat

As you can imagine from the prefix ‘poly’, this type of fat is one where there are several (at least two or more) double bonds in the fatty acid. The rest of the bonds are single ones.

The double bonds can’t have hydrogen attached, so they’re unsaturated. And because there are several places without hydrogen, the fatty acid is called polyunsaturated. Looks similar to this:

H H H H H H H

| | | | | | | unsaturated

-C-C-C-C-C-C-C=C=C=C=C=C

| | | | | | |

H H H H H H H

Examples of foods that contain polyunsaturated fatty acids are the processed vegetable oils like corn, sunflower, canola, soy, cottonseed, and also natural foods like nuts, seeds, and fish.

Because the double bonds can open up and allow free radicals to attach, processed vegetable oils are not stable, and tend to become rancid when stored for long periods. For the same reason, old peeled nuts go yellow and taste awful.

Frying with polyunsaturated oils

Using vegetable oils for frying is not a good idea at all. The heat opens the double bonds and unhealthy free radicals attach themselves to the food.

Free radicals are involved in so many disease processes, so why take the risk? Instead, use a stable, saturated fat for frying, like coconut oil, palm kernel oil, butter, or ghee.

Trans fats

Refined vegetable oils, and trans fats are the products of industrial processes.

Under certain conditions, when hydrogen is blown through polyunsaturated oils the double bonds open up and additional hydrogen molecules are able to attach themselves to the fatty acids. The polyunsaturated oil gradually becomes saturated.

In other words, a runny oil is artificially turned into a saturated fat, which can be spread on toast, and which survives for a far, far longer time on the supermarket shelf.

That’s not the only change.

In nature, when a double bond opens up and hydrogen atoms latch on, they usually do so above the normal plane. In the industrial variety, some hydrogen atoms always attach themselves below the normal plane.

Above the plane are called cis-fatty acids, and below the plane are called trans-fatty acids. This is a simple illustration of the difference.

natural cis-fatty acid:

H H H H H H H H H <——cis-

| | | | | | | | |

-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C=C-C=C=C

| | | | | | |

H H H H H H H

man-made trans-fatty acid:

H H H H H H H H

| | | | | | | |

-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C=C-C=C=C

| | | | | | | |

H H H H H H H H <——trans-

Cardiovascular disease

Does it matter if it’s cis or trans? Yes, it does. Trans fats are implicated in the development of cardiovascular disease.

Although there are moves to remove trans fats from processed foods, there are still many products on the supermarket shelves that contain them, so you’ll do yourself a big favour if you take the time to read the ingredients list. Your heart and blood vessels will be very grateful.

If you see ‘hydrogenated vegetable oil’ or ‘partially hydrogenated’ on the packet label, put it back on the shelf and look for one without the harmful hydrogenated fats.

Check also the labels on the vegetable oils and spreads to see if trans fats are listed. During the manufacture of vegetable oils, they are heated and subjected to chemicals, which often results in the formation of trans fats.

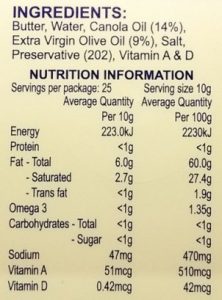

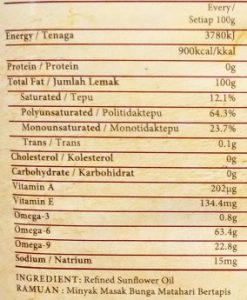

Here are two examples of many I found in local shops, containing trans fats:

butter+canola oil+olive oil spread sunflower oil

Omega 3 and omega 6

As I mentioned earlier, all fats can be classified according to the number of carbon atoms in their molecule, and the number and position of their double bonds. Most people are familiar with the two well-known types of polyunsaturated fat: omega 3 and omega 6.

The difference between omega 3 and omega 6 is the position of the double bond in the fatty acid.

The omega 3 molecule has its double bond 3 carbon atoms away from the carbon at the methyl end, like this:

carboxyl end-C-C-C-C-C-C-C-C=C-C-C-methyl end

(I’ve left off the hydrogen atoms to see the position of the double bond better.)

The omega 6 molecule has its double bond 6 carbons away from the carbon at the methyl end, like this:

carboxyl end-C-C-C-C-C-C=C-C-C-C-C-C-methyl end

Again, I’ve left off the hydrogen atoms for clarity.

It looks like just a small difference, but it has a huge effect. The double bond ‘pulls’ the molecule, resulting in a bent shape, a bit like crooking your index finger.

Obviously, the bend in the omega 3 molecule is in a different place from the bend in the omega 6 molecule, because the double bond is pulling from a different position.

The difference in bent shape contributes to each fatty acid’s characteristic properties and processes inside us.

Omega 6 and inflammation

After eating food with a lot of omega 6 fat in it (French fries fried in corn oil, for example) , enzymes get to work on the omega 6 molecules, gradually changing them into versions the body can use. There are two steps in the conversion, each controlled by an enzyme.

After the second step, the omega 6 fatty acids meet a fork in the road, so to speak. If they follow one fork, they form the building blocks for substances that help to turn inflammation off.

If they take the other fork, they form another fatty acid, called arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is a starting point for making substances that turn inflammation on.

Effect of insulin

If the insulin level in the blood is high, it stimulates an enzyme called delta-5-desaturase, which is the enzyme that controls the making of arachidonic acid at that fork in the road. Stimulating the enzyme cause more arachidonic acid to be made, which increases inflammation.

This observation is an important one, because most processed foods are high in omega 6 fats. And for decades we’ve been encouraged to use vegetable oils and vegetable margarines, which are laden with omega 6, instead of natural fats like coconut oil and butter.

In addition to omega 6 fat, factory-made foods and fast foods also contain a lot of refined carbohydrates, which are rapidly digested to glucose, triggering a big release of insulin.

Foods like this, for example:

The consequences of a combination of excess omega 6 fatty acids plus a lot of refined carbs, can be summed up like this:

high omega 6 fat + high refined carb => high blood glucose => high insulin level

high insulin level => high arachidonic acid => increased inflammation => chronic diseases

Omega 3 pathway

Omega 3 fats in food can be from fish, from green leafy plants, nuts, or from seeds like flax. There is a big difference.

The vegetable-origin omega 3’s are changed by enzymes, rather like the omega 6 fats are, but there are eight steps, instead of two.

At the end of the pathway two special fatty acids, EPA and DHA, are produced. Most people know the two abbreviations from the labels on omega 3 fish oil supplements.

EPA stands for eicosapentaenoic acid, and DHA stands for docosahexaenoic acid. Much easier to say EPA and DHA.

The eight steps to arrive at EPA and DHA from flax seed are quite sensitive, easily interrupted, and are not very efficient, so we don’t actually convert much of the flax oil into EPA and DHA.

The advantage of eating fish, or taking fish oil supplements, is that the oily fishes have already completed the pathways for us and hand ready-made EPA and DHA to us on a plate.

EPA and DHA

The two fatty acids EPA and DHA are used in the body in various ways, but I’ll not go into detail now. The post is already long enough!

Suffice it to say, EPA and DHA are very important for the healthy development and maintenance of the nervous system, brain tissue, and cell membranes.

They also influence greatly the process of inflammation. One of the ways they do this, is to inhibit the enzyme that controls the production of arachidonic acid from omega 6 (the one at the fork in the omega 6 pathway I mentioned above, that’s stimulated by insulin).

If the enzyme is inhibited, less arachidonic acid is produced, and less inflammation occurs.

Omega 3 and omega 6 balance

Because omega 6 tends to promote inflammation, and omega 3 tends to dampen it, the ideal situation would be to have about the same amount of each. A nice healthy balance.

In the days before the industrial revolution there were no processed vegetable oils or margarines. Omega 6 fatty acids (and some omega 3 fatty acids) came from real foods like nuts, seeds, green leafy vegetables, avocados, olives and olive oil.

Food from the sea provided omega 3 fatty acids, and there were healthy fatty acids from milk, cream, butter, cheese, yogurt, meats, and poultry.

It’s not difficult to imagine that whole foods like these provide a natural balance of fatty acids, more or less 1 omega 3 to 1 omega 6.

Nowadays the ratio is skewed because factory-made food is everywhere, and it’s usually high in omega 6 fats, especially fried and baked goods. And not many people eat fish regularly to get enough omega 3.

The modern ratio is about 20 omega 6 to 1 omega 3.

Or to put it another way, 20 inflammation-promoters to 1 inflammation-reducers.

No wonder there is so much inflammation-driven disease.

To sum up…

Both omega 3 and omega 6 fatty acids are necessary for humans.

We cannot make them; we can only get them from the food we eat.

Avoid man-made refined vegetable oils, fats, and spreads. They’ve been heat treated, chemically treated, have lost their antioxidants, and many contain harmful trans fats.

Instead, enjoy real, whole foods Mother Nature made, like fish, meats, poultry, milk, cream, butter, cheese, yogurt, nuts, seeds, leafy greens, salads, avocados, olives and olive oil.

They will provide you with a healthy balance of omega 3 and omega 6 fats, untouched by industrial processes…and you’ll thrive.

Pingback: Apple cider vinegar treats gastric reflux | Thrive Low Carb

Pingback: How to start eating the LCHF way | Thrive Low Carb